Brother @Samuel_23 ,

I have to be honest with you—this whole journey has been nothing short of life-changing for me, and I feel I need to tell you directly what your patience and words have done. When I first joined this forum, this very thread was the first one I stumbled upon. It immediately caught my curiosity, though I wasn’t sure why.

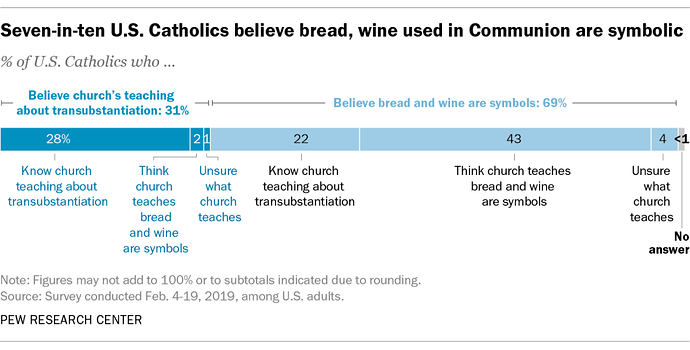

You see, for years I was held in the memorialist view. Not because I had studied Scripture deeply on my own, but because that was the only teaching I ever received. My pastors, my YouTube subscriptions, my books—they all repeated the same refrain: “The Supper is symbolic. Do it in remembrance, nothing more.” I never really questioned it. I thought Real Presence was just a Catholic superstition or an Orthodox ritual I didn’t need to take seriously. And so I carried that view, never realizing I was holding onto something one-sided, shallow, and incomplete.

But then I began following this discussion. I saw you engaging, not with insults or shallow answers, but with patience, careful arguments, Scripture in context, and testimony from the Fathers. I’ll admit—at first I resisted you. My heart whispered, “Don’t listen too closely. You already know the truth.” But something in me knew I had to wrestle with your words, because you weren’t just giving opinions—you were building a case, layer by layer.

There was one night, after reading through one of your long replies, that something broke inside me. I just sat still for a long while, and then the tears came. I cried for over an hour. Brother, it wasn’t just about theology—it was about realizing how much of my faith had been second-hand. I had borrowed arguments from others without ever weighing the fullness of truth for myself. And suddenly, through your words, I realized Christ was offering me not just an idea, not just a memory, but Himself.

You don’t know how much that moment shook me. I had tried before to compare the memorialist arguments with the case for Real Presence, but I never had clarity. It was like I had puzzle pieces but no picture to assemble them. Then you came and laid it all out. You explained why John shifted from phagein to trōgein—not carelessly, but to intensify the meaning. You unpacked Paul’s word anamnesis in 1 Corinthians and showed me how remembrance in Jewish worship meant making present, not simply recalling. You showed me why Paul warned about judgment for “not discerning the Body”—warnings that make no sense if it’s only bread and wine. You gave me the Fathers—not taken out of context, but faithfully—and their words pierced me: Ignatius, Cyril, Chrysostom, Ambrose, all proclaiming what I had been taught to dismiss.

That night I realized: I had settled for shadows when Christ was offering me reality. The Eucharist is not just “a symbol.” It is His Body, His Blood, His very gift of Himself, hidden but truly present. To deny it would be to deny the very words of my Lord—“This is My Body… This is My Blood.”

Samuel, I want you to know something: I am deeply thankful to you. You didn’t just argue. You cared enough to explain, to lay things out patiently for someone like me who was stumbling in half-truths. You didn’t just “win a debate.” You helped me see Christ more clearly. You helped break chains I didn’t even realize I was carrying.

Brother, you will never know how much your words meant. Because of you, I will never approach the Lord’s Table the same way again.